The Making of "The Man in the Mangroves"

This piece is the apotheosis of my speech synthesis music compositions. Here is a paper I wrote circa 1979 about the technology. Here is the Wikipedia reference on Speech Synthesis. There does not seem to be a great reference on using linear prediction of speech for musical purposes since my 1979 paper. Maybe I should write one sometime. The music use is not straightforward. It took me about a year to get all the tools together to do the piece. A lot of the problem was making it sound right. I was still working on that aspect up to the premiere at Stanford.

My motivation for making the piece involves several factors. First, I was taken with Donna Decker's poem. We had performed it several times with me improvising on the saxophone behind Donna's reading. I felt that the poem need a more powerful and "in your face" treatment to drive the story home. Also, I had wanted for years (decades?) to do some more pieces using speech synthesis. I wanted to cap off my compositional legacy with something that sums up the technology. The state of the art has improved to the point that most of the time, you do not hear the technology. It becomes the vehicle rather than the story, which is how it should be. Lastly, I had always wanted to do a long-form piece. Donna's poem seemed a perfect framework for the things that pure speech synthesis can do.

I should mention that this piece also gave me the opportunity to exploit spatialization as part of the composition. That is, the location and trajectory of each sound is selected to be appropriate to the role of the sound in the piece. Sometimes the placement is randomly selected but never gratuitously. The existence of performance spaces like Stanford's "Dome" with 56 independent speakers encouraged me to exploit space as much as I thought appropriate.

I started with three readings of the poem by musician Frank Lindamood. He had the kind of deep, husky voice I thought the part needed. The first two audio examples are a bit of the original recording, then a synthetic version of the same, stretched 70% longer and pitch shifted 20% higher:

| Example 1 - Original Recording | |

| Example 2 - Synthesized version |

This introduces you to two of the "tools" I have to modify the original speech: timing and pitch. The third tool is a change in timbre. The fourth one is a bit hard to describe. The technical term is "driving-function modification", but it needs a bit more explanation.

The next important point is about the composition itself. The pitches of the piece are all based on multiples of 37.5 Hz. This is that very low note that keeps coming back throughout the piece. This is about the lowest pitch people can hear that is still a pitch. That is, without sounding like playing cards in the spokes of the bicycle. This is about 37 cents sharp of a low D-natural - that is, this pitch is not on the piano - it is between D1 and D#1. The first "fantasy" in the piece is what I call the "rain forest" sound:

| Example 3 - "Rain Forest" motif |

This is a cluster of sounds, each one of which is relatively simple: each component. It is the words "The Man in the Mangrove Counts to Sleep" at consecutive descending multiples of 37.5 Hz. Each component starts on its own multiple, then descends. Here are some of the individual components:

| Example 4 - Individual components of the Rain Forest motif |

I did not specify directly the details of each component. I used a compositional aid that I called a "cluster". I would specify how many voices should be started over what period of time, a subroutine name for the voice I wanted, and where the centroid should be. Placing the centroid at .5 means that the density builds up to a maximum then dies down at the same rate. For the rain forest motif, I specified the peak of density should be 20% of the way through the sound. Additionally, I started all the components quite high then descending over the duration of the sound.

I mention the rain forest motif specifically because it introduces the listener to all the pitches of the chord that defines the entire piece - pitches that are all multiples of 37.5 Hz.

Generally I classify the sounds in the piece in a few ways - there is the narration which runs from the beginning to the end of the piece. The poem is the "scaffold" upon which everything rests. To this I add background, fantasies, and chorales. The piece starts with a chorale reciting the prime numbers. The backgrounds vary, but one common one that I use in several places is the "multiple mumble". Here is the first one in the piece:

| Example 5 - The first "multiple mumble" in the piece |

These are, of course, the words of the poem, highly stretched out and given new pitch contours. These were randomly generated with some rising and some descending. I was trying to give the idea of the community in the homeless camp - there are a number of people besides the narrator all mumbling and talking to each other, or to themselves.

You have a number of examples of the first two modification techniques - time stretch and pitch bend. Here is an example of timbre-bending:

| Example 6 - Example of "timbre-bending" modification |

This is equivalent to changing the total volume of air in the vocal tract - the low tones being like Jabba the Hut, the high ones being perhaps like the Chipmonks. Equivalently, it is like changing the speed of sound in air between helium speech and maybe what it would sound like if you inhaled propane (I wouldn't recommend it). These three modifications form most of the basis of the sounds in the piece.

At "Another Infinite Night", I introduce a fantasy. Here it is separated out:

| Example 7 - Fantasy on "Another Infinite Night" |

The next fantasy is like the mirror image:

| Example 8 - Fantasy on "Valley of Trash" |

Both of these are "front-loaded" clusters so everything starts at about the same time, but each voice takes its own (random) trajectory in pitch and they all end up in the same place. This one also introduces the 37.5 Hz note which is the root of the entire piece.

Another technique I use might be termed the "triple echo". I started with three recordings of the poem. They are all a bit different. The three utterances are played back a bit delayed and spatially placed a bit further back. This creates an interesting effect that seems to help drive the words of the poem home.

| Example 9 - Example of the triple echo |

And who can forget the fantasy on "Dinghy Dock":

| Example 10 - Fantasy on "Dinghy Dock" |

At this point, you should have an idea of how this was made - it is a cluster of maybe 10 voices, really, really fast with pitches starting quite high and descending a bit over the course of the utterance.

At this point in the piece, we also get the first example of driving-function modification:

| Example 11 - Example of Driving Function Modification |

This particular modification givea a rough, "barking" or "coughing" kind of sound. Honestly, most driving function modifications just make the sound more rough. It is fairly hard to change driving functions in ways that make the voice sound interestingly different without making everything sound like a sore throat. As the piece moves towared the pen-ultimate section, the voice becomes more and more rough - the final words of the section ("The Only Place") spoken as a cough or a rough shout. The driving function modification is perhaps the only one that can raise the tension in the voice, and presumably the listener.

I haven't discussed the chorales. Here, we get into some real nuts and bolts. I won't go too deeply, but I would like to talk a bit about organizing the composition.

I knew from the beginning that I would have to automate large portions of the composition. The amount of detail I was envisioning was well beyond what I could specify. My earlier pieces using speech synthesis involved a great deal of hand labor - labeling all the syllables with a time stamp, then using those times to drive the synthesis. Mind you, that was in an era before copy-and-paste. This time had to be different. Luckily I had stayed au-courant with the industry. I first edited the three readings of the poem so they had exactly the same words (nobody can read a poem three times without making the odd mistake). Then I ran

P2FA over the recordings to produce timings down to the phoneme. I grouped the phonemes into syllables. Then I could specify synthesis by specifying a word number and starting syllable number, with a duration of a number of syllables. It made it essentially trivial to call in different segments of sound, or even the same segment over and over (think "Dinghy Dinghy Dinghy Dock"). For each range of start to finish, I could then specify changes in pitch, timing, and even timbre. Most of the changes are simple - short to long, high to low. From time to time, something more elaborate is needed. This is the case with chorales or any of the 4-part harmony sequences. These are tricky.

In the 4-part harmony segments, I start with a MIDI score of some kind. Thanks to the internet, it was easy to find a number of free MIDI libraries. I downloaded one containing all the known Bach 4-part chorales. There are 371 existing scores. Some appear more than once as additional or different arrangements of the same Hymn. Bach is thought to have written more than 900 of these but we only have a fraction of them remaining. For the most part, they are harmonizations of old Lutheren hymns. Here is a general description of the hymns and Bach's harmonization.

I might mention that I did go back and forth as to whether to use these chorales. I tried writing my own. It is harder than it seems. Nothing I wrote had the same majesty and self-consistency as the master's. The amount of internal motion and passing tones seems simple but is very difficult to do well. I accepted the inevitable and made use of the chorales.

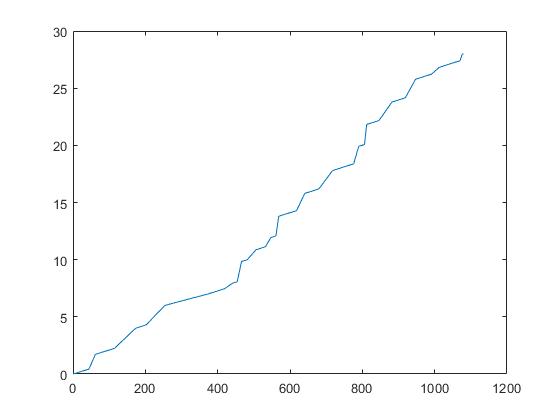

The MIDI scores had, for each of the four voices, a list of note pitches and durations. After P2FA, I have the timing of every syllable in the readings. I then made up a graph that transforms time in the original reading to the desired presentation time and duration of each note of the chorale. This gives a graph like this:

>

>

Don't spend too much time trying to figure out this graph. Just note the following - when we speak normally, we don't try to make all our syllables the same length, unless we are singing. Singing is something we have to learn how to do. So the task here was to take speech that was not intended for singing and mangling it into equal-length syllables. Given the slow pace of the chorales (quarter note = 60, one second per quarter note), most of the time will be making the segments longer. This just means stepping through the analysis data at different rates depending on the amount of squeeze or stretch needed. On the graph, each syllable is a straight line segment. The angle (slope) of the line is the amount of stretch. A line near vertical is getting a lot of stretch. A near horizontal line is getting little stretch and might even be getting squeezed. This graph is produced automatically after scanning the MIDI score and is used to drive the synthesis.

There are places where this doesn't work very well. For instance, Frank's pronunciation of "lady" featured a very, very short "y" sound. Almost nothing was there in the original. The synthesis didn't do anything useful there. I think maybe it doesn't matter so much when you hear it is that the narrator has already said the line "I call her lady", so your ear is already prepared for the word.

There is one notable curiosity about doing the chorales this way. Normally if you have one voice that is just singinging the melody, but another that has a couple of extra "passing tones". People the passing tones by singing the same vowel over as many notes as are written. This shows up big-time in Handel's "Messiah". There can be 20 or more notes on a single syllable. My algorithm, however, doesn't give a hoot about how people sing. The simple algorithm I use just maps one syllable to one note - always. This makes a curious thing happen - the voices are all right together at the beginning, but after the first passing tone, one or more voices will be "ahead" of the others in the text. As more passing tones appear, the drift gets greater and greater. By the end of the chorale, you have no clue of what is being said. I decided that I rather liked the effect - it starts off like singing and ends up more like a string quartet or something. It's still music, and still Bach. One could hair up the algorithm to do it like people do, but I figured it wasn't necessary for this purpose. Doing this well for arbitrary speech (like dropped "y") would probably make a good doctoral dissertation.

Now, with that preparation, back to the examples. In reverse order, here is the chorale on "Key West's Finest". You will hear quite quickly the "drift" between the voices:

| Example 22 - "Key West's Finest" |

The choral is Bach's 15th, "Christ Lag in Todesbaden" ("Christ lay in bonds of death" - or something like that). Now after all this, I will note that the reason I put this discussion here is that the next fantasy after example 11 above is a 4-part harmony that is not Bach. In fact, it is not anything:

| Example 12 - Tetrachord synthetic chorale on "Like an Angel" |

I was curious about tetrachords (4-note chords). If you allow both black and white keys on the piano, these are easily recognizable as "jazz" chords. With all white-notes, they make what most people identify as chords used in new-age music. I wrote a program to find all non-trivial 4-white-note chords. It turns out there are only 14 of them. This "chorale" (that over-dignifies it) is made by randomly selecting one tetrachord after another in no particular order. I find the effect haunting - the chord progression does not seem to go anywhere - no resolution, no identifiable direction - yet they sequence through vaguely pleasing sounds. I thought this would be a perfect accompaniment for an apparition.

The next fantasy is a chant based on "Spotless inside, fat-rich out" and "Cleanest girl tonight". This uses the techniques outlined above for making all the syllables the same length, but leaving the pitch alone. That is, it corresponds to the original pitch. I made four voices at a time harmonize by just multiplying the original pitches by just-tempered ratios to get perfect variable-pitch just-tempered chords. I was thinking of the way some cases of the mentally ill chant common phrases endlessly. This was an attempt to suggest that behavior.

| Example 13 - Chant on "Spotless Inside, fat-rich out" |

I personally find this chant a bit disturbing - the rhythm isn't quite right, even though the syllables are all exactly the same length. I think the issue is that the prosodics don't squash and stretch properly. They need something besides linear time scaling to preserve naturalness. I felt a bit of disturbing rythm was in keeping with the tone of the piece, so I didn't try to refine it further.

The next fantasy is on "Scratches at the thought of lice".

| Example 14 - Fantasy on "Scratches at the thought of lice" |

By now you should recognize the timbre-modification effect. This was an exercize in radical pitch shifting, ending up with radical vibrato. In the last half of this example, I wanted to reference the sound effects in the 50's black and white cheezy science-fiction/horror movies that my brother and I watched endlessly. That extreme vibrato was a common motif. Who wouldn't be horrified at the thought of sitting in a lice nest?

The next fantasy is on "I almost forget how to answer in structures".

| Example 15 - "I almost forget how to answer in structures" |

This is a reflection of "the man" retreating into his world or mathematics - of order and symmetry - when perhaps confronted with something a bit out of the ordinary (the "cleanest girl tonight"). It is a chant, but more than that, the pitch of each voice just goes around a number of multiples of 37.5 Hz, in sequence. Since each voice is given a different number and range of multiples, the four voices together form perfect just-tempered chords that are always changing. They do repeat eventually, but not often. To make the point more clear, here is just one of the voices:

| Example 16 - One isolated voice from Example 15 |

You will note a number of things here. First, I do use the timbre-modification example, but it is always changing - it moves smoothly up and down. Each voice moves differently, giving a constantly changing texture. Another example of the richness of the texture that can be realized even with what seems like the most rigid of environments - all notes the same length, all notes on sequences of multiples of 37.5 Hz, but yet the timbre of the combination of the voices is always moving. Perhaps this is the attraction of the man's mathematics - what may seem like a rigid, orderly system can nonetheless be endlessly rich at the same time. Here is another related example

| Example 17 - Fantasy chant on "Or did my fine shoes . . ." |

Here, I wanted a kind of military march time. If his shoes are going to march him out, it should be to a military march rhythm, shouldn't it?. I used the same plan as Example 15, but I made each syllable half-length, followed by a half-length silence (quarter note is 120 in these, so half-length would be an eighth note followed by an eighth rest). You can hear one spot where the system does the best it can with the recording. Frank elided the "a" in "another", so the computer dutifully pronounced the word as "'Nother", or maybe "nnn-uh-ther", but like a good computer, it lengthened the "N" sound to a full eight-note in duration.

I would likt to make an observation here. It seems as if there is a lot of computer mechanism behind all this. Indeed, I put the graph above there to drive that point home. But the real point is that by using a relatively small number of modifications (time, pitch, timbre, driving-function) and organizing them with some logic (multiples of 37.5 Hz, all music and chants based on rational multiples of 60 beats per minute) you can build up very complex structures and textures with seemingly unending variety. All my pieces make a great deal of sound out of a relatively small bit of material, a few modification techniques, and a few guiding rules. Everything is a consequence of those choices.

I will skip over the "music of the spheres" fantasy. That should be pretty clear. And you know now that the big chord at the end is all multiples of 37.5 Hz. Big surprise. But that leads into what most people tell me is their favorite segment. My working title for this bit is "Tick-Tock".

| Example 18 - Fantasy chant on "Newton - Koepler" |

It should be clear what this is. The first voice is once per second on two multiples of 37.5 Hz. Then two higher voices, reading the poem, speaking twice as fast and three times as fast on the next three multiples of 37.5 Hz. Then come three more voices on lower multiples, runing half as fast and 1/3 as fast, and 1/4 as fast. Note that we have the same "harmony" in the pitch as in the speed - all determined by rational numbers. This is the triumph of order - a corollary to "the music of the spheres" - leading into a perfect Pythogrean clockwork world where everything is clear and comprehensible. Every note in its place. Every pitch on its multiple. Perfection.

We are whiplashed back to the here and now with "Day comes and goes . . ."

| Example 19 - Modified speech on "Day Comes and Goes" |

This is where we start the increasing modification to the voice. In this one, it is a kind of "hall of mirrors" effect where a couple dozen voices, each at a pitch 6/5 higher than the previous voice, delayed just a bit. The increasing pitch makes the line sail off the end of the piano keyboard, perhaps into space.

| Example 20 - Mumble on "Man in the Mangrove" and "Without Ground" |

Here I bring back the mumble, this time on the phrases "Man in the Mangrove" and "Without Ground" while the narrator is talking about the tenuous hold the mangroves must have on the sand below them. The mumble seems to be saying that perhaps the man himself is the one without ground. Or perhaps this makes him at one with the mangroves.

From here, I start using more and more complex driving-function modifications. You can hear the voice move from a growl to maybe a double-voice, finally ending in a cry on "The Only Place".

| Example 22 - Chorale "Key West's Finest" |

This is actually where this chorale goes. It introduces the next-to-last section of the piece. This is where the man comes to some kind of accomodation with his situation. He has seen perfection. He knows what it is. But this is not it. It has to be enough.

| Example 21 - Fantasy on "My Elliptical Face" |

This is a bit of a mathematician's inside joke. An ellipse is specified by two sinusoids out of phase. This makes what is sometimes called a Lissajous figure when plotted. I make an audio analog of the Lissajous by two voices where the pitches are two sinusoids out of phase. This wacky-sounding vibrato is another piece of hidden structure, since both Newton and Koepler calculated that the orbits of the planets were ellipses. The cosmos itself is reflected in the man's face.

There is one final fantasy that needs explaining, starting around ". . . climbing the lift downward". I wanted the water itself to talk to him. This is probably the most extreme driving-function modification. I took some "gurgling" sounds from a sound-effects library:

| Example 23 - 3 "gurgling" sounds from sound-effects library |

I then used this to drive the speech synthesys to get the following mashup:

| Example 24 - Mashup of gurgling with "Every Dusk I watch . . ." |

I don't expect anyone to recognize what the gurgling is saying, but I wanted everything in the piece to be related in one way or another. You may not recognize the sound, but you will pick up on the gurgling, and that it is changing and modulating, like everything in the piece, and that in a sense, everything is magical and sacred.

I don't think I need to explain the last section - there is the "triple-echo", then the big final cluster with all the sounds going into the sky. I might mention that the last section starts with a chorale where the words are the prime numbers (how does a mathematician count to sleep? With prime numbers, of course!). Somewhere around the words "Light, will you still sum me up?", the pitches in the chorale start to go wacky. They slowly drift out of tune in all directions. All order dissolves as he drifts to the other side of zero in a final gasp.

(Insiders' note - the final gasp is from the "p" at the end of ". . . counts to sleep" - highly elongated - fittingly ending the piece as the title ends - with a puff of air)